Mugdha Pendharkar

The Urban Care Crisis in India

Over the last decade, the rate of urbanization has swelled to approximately 34.5%% in India. This rise in urbanization has raised pivotal questions about lifestyle, upbringing, and care. For years now, especially in Asian countries, care work has been pushed under the rug as something of meagre importance and implied responsibility, with the majority of the workload being pushed on the shoulders of women. However, more cities are seeing a redefining of a lot of aspects of lifestyle, and as a result, care work is revolutionizing too. With revolution, comes opportunity— this restructuring has created room for researchers to understand and analyze the various facets of care work.

| Care economy encompasses the paid and unpaid activities, labour and relationships that sustain human activity. Care economy intersects with the achievement of the UN SDGs —especially SDGs 5 & 3— and reflects as a salient determinant of a country’s quality and the population’s well-being (World Economic Forum) |

The average Indian household constituted 6.37 members in 2006, but by 2022, the typical Indian urban family had shrunk to 3.09 members. Inescapably, this shrinkage has increased pressure of taking care of children (and the elderly) on primary caregivers– in India, women. Also, India has seen an increasing life expectancy (~69.2 in 2009 to ~72.9 in 2022), leading to a growing need for caring for the elderly as well.

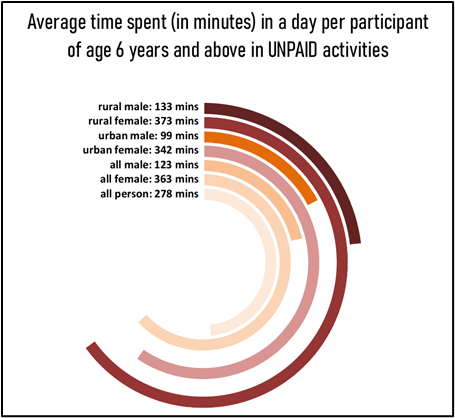

The archetypal urban female spends 342 minutes in unpaid care work as compared to the urban male who only spends 99 minutes on an average in a day, according to the Time Use Report of India of 2024.

Such disproportionate changes are not only unfair but have also been observed to be without any societal recognition or support from other family members. The implied responsibility undoubtedly takes a toll on women’s physical and mental health, decision-making abilities, and productivity– both personal and professional.

| Time poverty in its essence is a lack of sufficient time to work on pursuits that interest the self: engaging in activities that contribute to one’s well-being and development. Such inordinate distributions of time between men and women, especially in urban settings, where in most cases both partners are working— leads to women being excessively more time poor than their male counterparts, often leading to burnout, fatigue, and inefficiency. |

The Labour Force Participation Rate in urban females was reported to be 25.4% in June 2023, a 24.5% rise from 20.4% in June 2018. One would think that the increased participation would lead to an increase in the share of responsibility between men and women— unfortunately, statistics in India tell otherwise. The typical Indian woman is still juggling the majority of unpaid care work now in addition to paid labour work and now with a growing paucity of traditional joint-family structures and increasing nuclear families, the pressure is more than ever.

Another consequence of the increased LFPR is a significant rise in demand for paid care services. However, even that aspect isn’t devoid of impediments for most. Despite a rise in dual-income households, the paid care industry continues to be unreachable for many. Paid quality care has become expensive because of factors like a lack of qualified caregivers, costly safety infrastructure, and in case of child & infant care: development of exceptional curricula that cater to parents’ demands & expectations, and other regulatory compliances that premium institutions need to meet in order to gain parents’ trust.

Though still emerging in the global care economy conversation, India is steadily developing its own frameworks and responses to caregiving challenges. According to the India Employer Forum (2023), investment in India’s economy could generate 11 million employment opportunities of which more than 30% would be for women.

Most parents work full-time 8 hour work days, which requires paid care services that offer similar time schedules too. Premium care services in Bangalore. which include meals, transport, and other structured activities accommodating an 8-hour time timetable cost roughly Rs. 10,900 per month, with similar fee ranges demanded in other metro cities of the country too. Parallelly, senior care in tier II cities is facing an identical landscape: typical average costs range from Rs. 10,000 to Rs. 35,000 per month. A NITI Aayog report on the situation of senior state care estimated that the senior care industry is about $7 billion. Numbers like these indicate the potential of the paid care industry.

Despite the observation of an increase in dual-income households, income inequality in India cripples many. Premium quality care services take up almost 10-20% of the income of lower middle income households in urban settings. Huge expenses prompt middle income households to switch to substandard, more informal alternatives that don’t promise good results and often pose safety issues.

Beyond Borders: Care Work in other countries

While the world is still digesting the concept of care economics, some countries have stepped ahead and made recognizable changes that have brought about significant development in the field.

- Nordic countries (Sweden, Finland etc.) have been notable torchbearers in endorsing care work.

- Sweden confers a healthcare system to its people that is largely tax-funded, decentralized, and checked to the best quality that the country can offer; universal access to subsidized child care, a very reasonable parental leave (to both parents) of 480 days and offers interesting government programs like income-based fees and the fourth child exemption.

- Finland, on the other hand, offers a municipal support model – family members who care for the elderly or the disabled full-time are provided with a ‘formal caregiver’ status and given exemptions and concessions for their services, along with flexible work arrangements.

- Latin America has been an emerging partaker too. Santiago and Quito are building care lattices that integrate child care, eldercare, healthcare, and employment– trying to build an all-inclusive system that can benefit all parties.

- Colombia has legally acknowledged the economic contribution of unpaid care work in one of its amendments of 2010.

- As far as eldercare is concerned, Japan’s aging population aids the growing eldercare market– demand for eldercare services, assisted living, in-home services are on the rise. The Japanese LTCI (Long-Term Care Insurance) system has proven to be an efficient provider of a range of services to support the aging population and reduce the burden on primary caregivers.

India’s Changing Ecosystem Towards Urban Care

In India as well, many cities have introduced interventions that enable the various facets of care economics to generate a beautiful interplay that ensures accessibility, inclusivity, and equity. Government provided creches are available under the Anganwadi centres and Palna scheme. Private sector organisations are mandated to provide onsite creches under the 2017 amendment of the Maternity Benefit Act.

- Kochi is known to conduct gender budgeting programs so that enough policy steps are taken to reduce gender inequalities in the country.

- Kakinada, on the other hand, utilizes inputs from gender experts on programmes to track how resources are being distributed and whether they are closing gender gaps in fields like health, education, and employment.

- India has also recognized the gravity of senior care and its growing need in the country. In response to estimates that suggest India’s elderly population is expected to reach 347 million by 2050, India introduced schemes like the National Programme for Health Care of the Elderly (NPHCE), Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension Scheme (IGNOAPS), and the Atal Vayo Abhyuday Yojana (AVYAY)

- Many organizations have also established senior living communities with facilities designed to be accessible and elderly and disabled-friendly. Travancore Foundation in Kerala has already instituted senior living communities, presidency homes, and retirement homes in various areas of the city. Nonetheless, state governments and policymakers need to understand and prioritize the development of accessible senior care infrastructure sanctioned by the government that ensures equitable access across socio-economic strata of the country.

Conclusion: What does a caring city look like?

The importance of care work remains hidden from plain sight because of its ubiquity. Given that care work is so precarious to deal with because of embedded social implications, gender expectations, and significant opportunity costs, it becomes difficult to fit it into a conventional policy framework. Unpaid care —though significant— is not accounted for under any specific economic metric and therefore remains outside of policy discussion and discourse. Invisibility in urban settings becomes a corollary to this lack of scrutiny.

All of this demands an important question: what does a caring city look like? Is a city called caring simply because it offers access to amenities and delivers comfort to a certain extent, or must we also ask how its residents’ needs are acknowledged, supported, and whether they are truly affordable or not.

In reimagining urban settings through the kaleidoscope of care, there are certain ameliorations that a city must inculcate to truly expose its residents to the nuances of paid & unpaid care work. At the root of care work lies the poison of stereotype: urban spaces must start by ungendering care work. Care work in its truest sense is a responsibility, but it’s not a responsibility that’s innate to a particular gender. The exhaustion that comes with the nature of care work is a pressure on both genders and there is an urgent need to dismantle the stigma that surrounds it.

However, cultural change needs to be accompanied by structural reform. Cities need to transform into spaces that are accessible to elders and the disabled. While much work is being done on making washrooms and private spaces accessible to new mothers (with breastfeeding areas and sanitary care specifics for infants), it is imperative city planners also realize the need for building an equivalent for new fathers too, such that infrastructure truly serves all forms of caregiving roles.

Cities must also enable caregiving by men, as fathers and sons. There is need for policies and laws to help redistribute care work fairly between partners (like paternity or family leaves). But, in addition, Neighborhood- or worksite-based parks, creche, feeding and changing rooms, and other facilities must be provided in urban areas for all working parents, not just mothers.

The lack of quality paid care also remains an imperative lacuna, critical to reducing the unpaid care burden. A solution could be introducing skill development or skill enhancement programs for individuals who wish to provide paid care work services in cities. Through these programs, they will be trained (and certified) to give quality care: an initiative like this would professionalize the care sector, generate employment opportunities, and subsequently create more certified caregivers— thus helping in building a system that would be more affordable than previously.

Although the country still remains in the early stages of institutionalizing care economics, the pace with which we progress is discernible. India’s sheer scale: demographic, cultural, and the scope of its policymaking puts it in a unique position when navigating the unique challenges of care work and social infrastructure. Notwithstanding, India possesses the capacity and the impetus to further develop its policy frameworks, initiatives, and structural reforms in ways that could significantly revolutionize the state of care work in the country. What remains is the will to act.